|

|

|

|

|

|

Making 3D Terrain Maps

|

|

|

|

|

|

< Previous Page----Table of Contents----Next Page >

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

--Camera: Direction

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Selecting a direction of view is your first decision when setting up a 3D scene. All factors being equal, I prefer a camera direction looking from south to north for compatibility with conventional maps that usually are north oriented. In general, the smaller the map scale, and the less familiar the place, the more reason for selecting a north looking view. For example, many of us would not recognize Ethiopia in a view looking south, but we might have a chance if the view looked north.

Staying on the subject of small-scale maps, rotating a scene by, say, 10, 20, or 30 degrees from true north (to either the east or west) can bring interest to a scene while still maintaining geographic familiarity. You often see maps in National Geographic magazine that do this very successfully. Rotating the direction of view from north can give you more options when positioning a 3D map in a graphical layout, especially for geographic areas with an unusual or unbalanced shape.

Map focus is a key consideration when choosing a direction. From bottom to top on the page, 3D terrain maps have a foreground, middle ground, and background. Try to place the most important information in the upper foreground (do not crowd the bottom of the page) and middle ground. The background is for geographic context and graphic balance.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

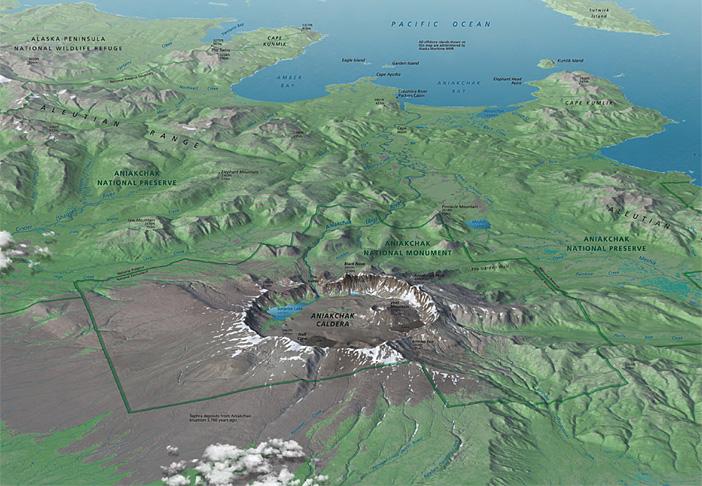

Aniakchak National Monument, Alaska, with north orientation. Although artists avoid centering the subject in a painting, it is accepted practice on 3D terrain maps. (Click map to enlarge.)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Unique terrain characteristics are a valid reason for selecting a camera direction other than north. On the Aniakchak map above, a southeast-looking view reveals the Aniakchak River flowing through a breach in the caldera wall to the Pacific, a route taken by river rafters, among the few visitors to this remote park.

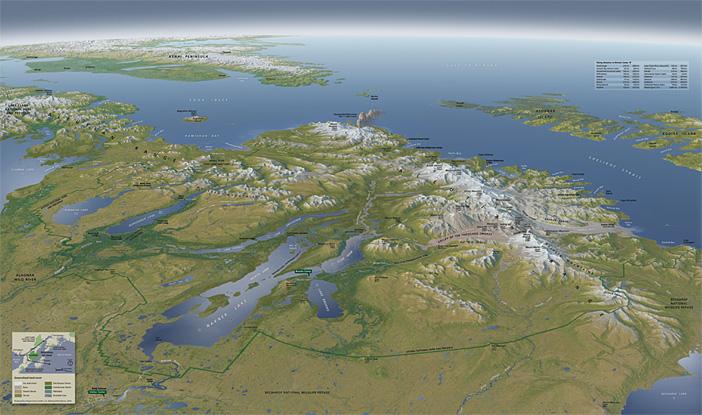

Graphical composition is another reason for choosing a non-north view. For example, a northeast-looking view of Katmai National Park (see map below) takes advantage of the parallel lake and ocean coasts that are perpendicularly aligned, intersecting at an implied "X" near the center of the scene. The lake alignment is further implied by an erupting volcano plume that points through a gap in the coast toward the empty Pacific. This view direction also conveniently provided space in the lower left and upper right corners for an inset map and distance chart.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X marks the spot: Katmai National Park, Alaska, looking southeast. (Click map to enlarge.)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

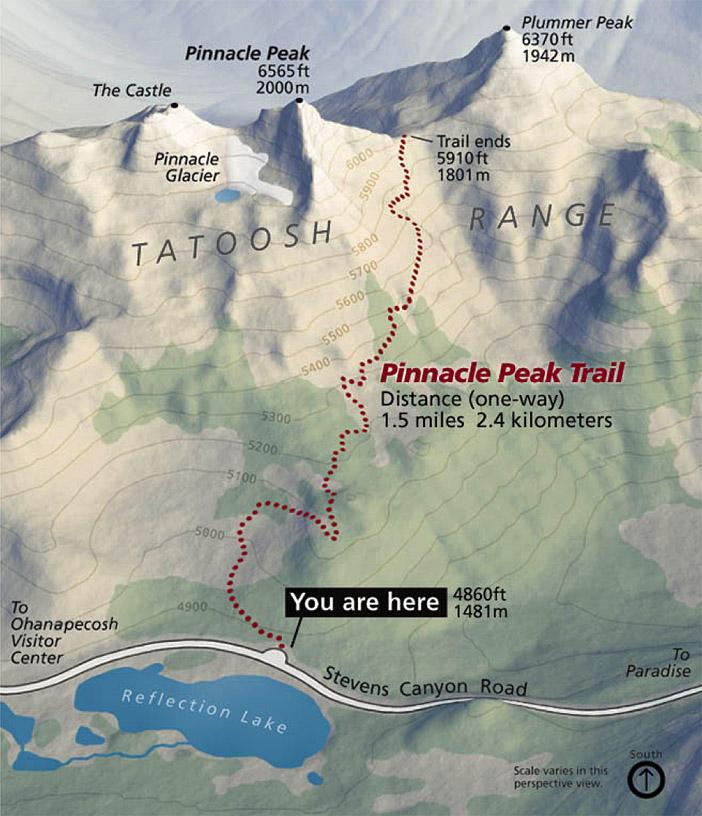

Large-scale 3D terrain maps used for site navigation are best served with a camera direction that looks in the direction of travel. The National Park Service employs site-specific views for trailhead maps. The map, sign on the ground, and person reading it is oriented in the same direction as the trail (see Pinnacle Peak Trail map below). Tightly cropping the map focuses attention on only those geographic features relevant to hikers.

Don't look down

Avoid a direction of view that looks down slope on a terrain. For example, the view from the summit of Pinnacle Peak to the trailhead at Reflection Lake, would not work as well as the opposite view looking up. In downhill views, because the terrain would falls away from the reader, foreshortening is severe. This limits the mappable area. Downhill views also can be disorienting. When it comes to terrain, most people are accustomed to looking up.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pinnacle Peak Trail, Mount Rainier National Park, Washington.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Satellite image shadows

Most satellite images and aerial photographs are taken in mid morning (there are fewer clouds and less haze at that hour), which places shadows on northwest-facing slopes in the northern hemisphere. On 3D terrain maps draped with satellite images, the embedded shadows interfere with views that look from north to south—slopes facing the reader will be dark and lack detail (see example below, lower image). You will instead have to use a view that looks generally from south to north (top image).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A 15-meter Landsat 8 image draped on a 30-meter DEM of Crater Lake, Oregon.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

< Previous Page----Table of Contents----Next Page >

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|